There's not a big market for Bibles in Latin.

A Nation is A Narrative, Part 2: A whistle-stop introduction to the emergence of the idea of the nation state by way of print-capitalism and colonialism.

Have you ever wondered why we have nation states?

Probably not, because one key part of the idea of the nation is that it has existed for a long time. Except it hasn’t.

As I discussed in the introductory part of this series of A Nation is a Narrative, there are some very crucial differences between the modern nation state and the political and social units that preceded it, despite our sense of their continuity.

In fact, some of the nation states that appear most obviously discontinuous and wear their ideological creation on their sleeve, are actually some of the forerunners of the modern nation state: the nations that grew out of the settler colonialism in the 18th century.

To Benedict Anderson, as outlined in his book Imagined Communities (first published 1983), the confluence of colonialism and the idea of the nation is not coincidental – rather they are both linked to modernity, if you want to be euphemistic, or capitalism, if you don’t.

While most, if not all, of the elements that gave rise to capitalism also developed elsewhere, it was a particular combination of technologies and ideas that made Europe the growing ground for both the modern nation and the largest colonial project the world has ever seen: techniques of navigation and cartography, development of transportation and industry, and, most crucially to Anderson, the invention of the printing press.

To Anderson, what he calls print-capitalism, i.e. the mass production and consumption of written material, is the single most crucial factor in the development of the nation. As I outlined previously, before print the languages of rulers did not reflect the language spoken by the majority of people being ruled: official languages allowed communication between those who took decisions that had little impact on the daily lives of the majority of people.

The Bible in Latin was the first book that Johannes Gutenberg printed in the 1450s using moveable type, which allowed for quick and cheap printing of more than one manuscript on the same equipment. This technology, and the fact that there was a limited market for Bibles in Latin allowed and encouraged printing of other books in other languages. The availability of printed material in vernaculars increased literacy and increased literacy drove the sense of a shared language as well as the sharing of ideas.

It was this, argues Anderson, that allowed us to imagine being part of societies on a larger scale than before, beyond our immediate communities, through a sense of belonging circumscribed by language. Mass printing also meant a possibility of access to power, by allowing people to understand how they were being governed, and by enabling their (at least theoretical) involvement in that government. Thus, with the invention of printing, two key aspects of the modern nations state, that of a “people” and that of their right to self-determination, emerged as ideas.

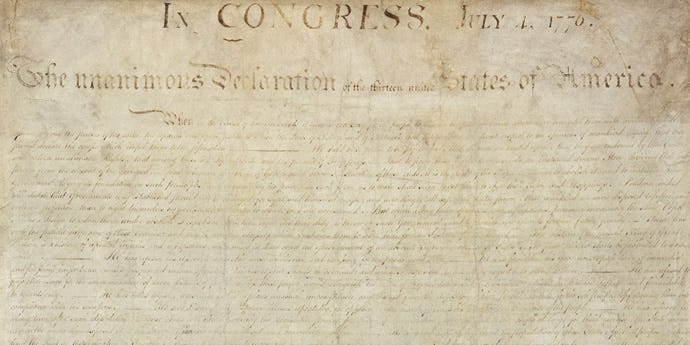

Benedict Anderson traces the first manifestations of these nascent ideas of nation to the to the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776, and similar declarations following on in Latin America.1 Undoubtedly, both the territorial separation and the wish for management of their own affairs (read businesses) of the settler colonies pushed the early ideas of nation to take political shape in the Americas before they first did so in Europe, with the French Revolution 1789.

It is striking, of course, that with the settler colonies, ethnicity or linguistic and cultural heritage is not central to the nation, not, at least, in theory. However, the idea of a “Manifest Destiny” to establish a Great Nation, is.2 So we also see the emergence of the colonial logic of the superiority of the nation state in justifying the subjugation (and eradication) of people that do not have a nation.

In Europe, meanwhile, the nation becomes increasingly linked with culture, as a number of primarily linguistic groupings, within loosely defined territories part of multi-ethnic commonwealths or empires, are all looking towards the new trans-Atlantic model of national self-determination. This is where the great age of imagining various, distinct, national histories begins, in order to carve out the right to exist as a nation by appealing to precedence and continuity – I will say more on this in future posts as this is exactly what preoccupies me in Stockholm.

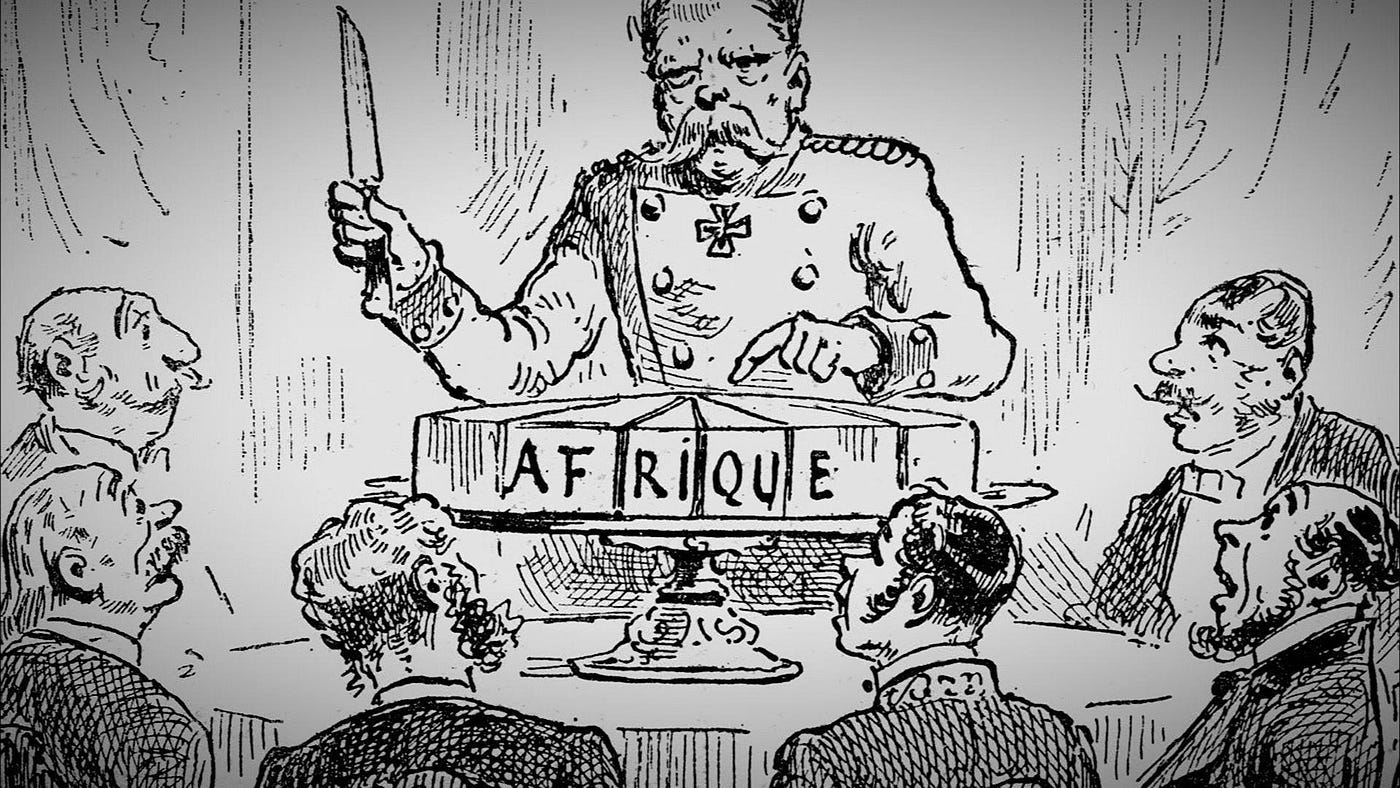

Although Anderson views European imperial colonialism of the 19th century as a lagging remainder of a pre-nation state order, it seems to me that the race to fill the “blank” spaces on the world map pushes development of European nations further – witness the scramble for Africa in the late 19th century as a major driver for the unification of Germany in 1870. In addition, this wave of colonialism continues to establish the hegemony of the nation state through the colonial logic of superiority, although where conquest is not possible, administration takes its place. The argument now goes, for example in British India, that the people under colonial rule are simply incapable of efficient government on their own, but must be supplied such through proxy rule by a nation state.

In this era the technology of mass print continues to be crucial – not the least in education and the role it played in both nationalism and colonialism. Mass education, in particular mass literacy, was key to the rise of the nation: what better way of creating a sense of unity, of ensuring adherence to ideals, norms and rules, and of supplying the nation with the workers, administrators and leaders it needs? Not to forget the usefulness of mass education in inculcating the population of a colonial empire the superiority of the culture of the “home” nation in the population of a colonial empire.

In the next part of A Nation is A Narrative I will look in more detail at how language emerged as a crucial marker of nationality in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Declaration was printed on 4 July 1776 and distributed to be publicly read. Within days it also appeared in printed newspapers.

The phrase “Manifest Destiny” was coined in 1845, and became the name for the belief that the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion across the continent, driving territorial expansion in the 19th century.

It was so good to read about Benedict Anderson after years! Thank you! I love how you are delving into this at this time. The point that a community is imagined doesn't make it less real spoke to me. We can apply Anderson's theories to so many current conflicts which are on at present.

*Absolutely