A Nation is A Narrative

I have been writing about how countries are made of stories for a while, but current events made me write a post about why the nation is a concept that needs radical rethinking - now more than ever.

Then I rewrote it.

I was trying to voice, succinctly, that the idea of the sovereign nation-state was born only a couple of centuries ago out of specific economic and historical circumstances which mean that the system of nations as it exists today perpetuates global inequality and instability.

However, feedback from my long-suffering beta reader made me realise that I need more than a thousand words to do so. So here is an introduction to a series of posts which will trace some of theory of the nation and the possibilities of post-national thought that have been influential on my work.

In this post I want to define what I mean by the nation, and very briefly outline why it is different from what came before (in under a thousand words!). One of the key aspects of the nation is that it invents for itself a continuous past in order to legitimise its present, so it is hard for us to think about history without nations.

The modern nation-state can be defined as a “territorial political community” or “territorially bounded sovereign polity—i.e., a state—that is ruled in the name of a community of citizens who identify themselves as a nation.” It is this unique concatenation of defined physical space, representative authority and self-defined cohesion that makes a nation-state: in particular the way these three things legitimize each other.

There were states before: kingdoms, chiefdoms, empires, autonomous cities and territories, and confederations of smaller units such as tribes and principalities. These, too, were concerned with territory, and power, and to a certain extent community. But our idea of kingdoms of yore as coherent communities coalescing around a king ruling over defined lands that pass to the hero who marries the princess is a fairy tale (and indeed, such fairy tales played a part in the making of nations).

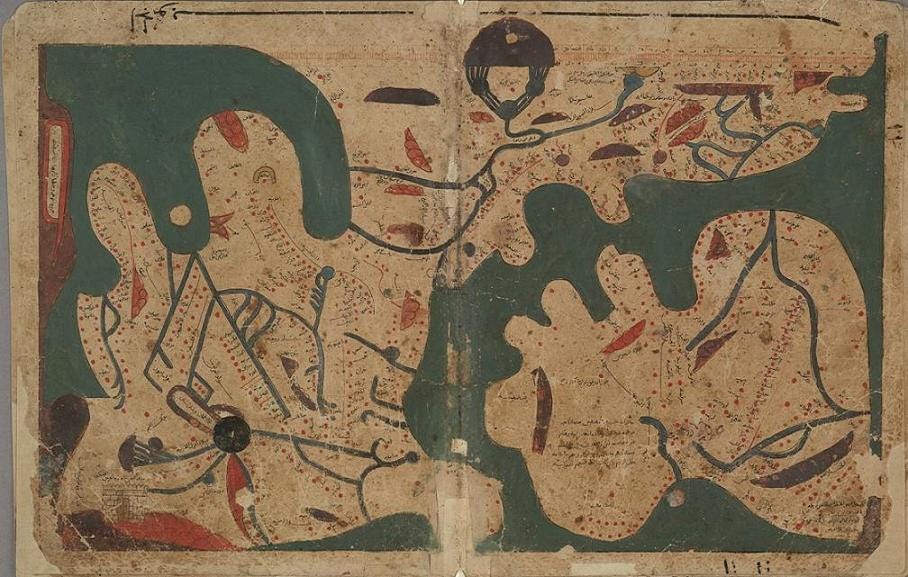

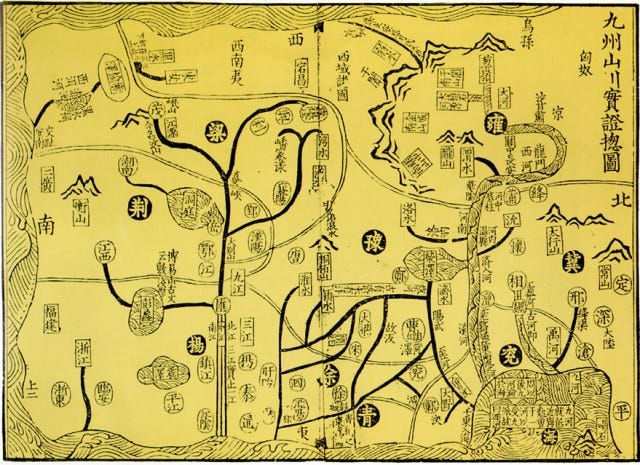

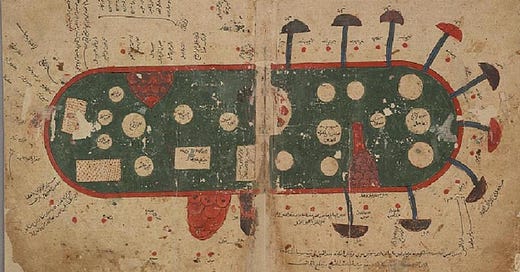

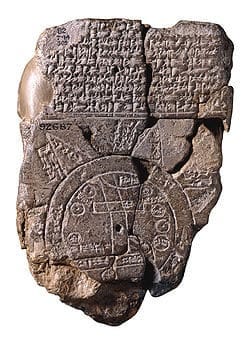

Before advances in navigation and cartography (not only in the West) a state’s territory was more nebulous, often non-contiguous, and always in negotiation. Power was almost always religious or dynastic or both. Communities were local, ruled by leaders or lords whose allegiances to kings and emperors had little impact on their subjects. Law and order was mainly dealt with in communities or regionally. Any central administration tended to regulate fealty and taxation arrangements between kings and feudal lords.1

Countries (in the sense of ruled territories) were made and unmade by marriages and heritage, and came together in diverse and polyglot commonwealths and empires. Researching Stockholm made me realise quite how interconnected the royalty of Europe are: there is little sense in talking about the ethnicity of any particular royal or imperial house.2

Outside the elite there was scant sense of belonging to a larger cultural unit, beside communities of faith. The ruling classes shared a language, but this was not necessarily that of their subjects, or even their own, but provided instead by religion, e.g. Latin in the Holy Roman Empire that covered most of central Europe in the 13th century, or by accidents of dynastic foundation, e.g. Chinese koiné3 being kept as the official language during centuries of the Chinese Empire, even as differently ethnic dynasties came and went.

The pre-national state is thus a vertical construct: authority flows from above, from God via the absolute ruler.4 Who is being ruled and where is less important. The nation-state in contrast works through a kind of vertical circle of legetimation: state authority extends across (but not beyond) a delineated territory, to all citizens equally, it flows from the people (at least nominally), whose cohesion as a community comes from the idea of being a nation, that is, being citizens, by dint of that authority, of a particular bounded territory.

It is this circle that delineates the modern idea of sovereignity (as opposed to the older meaning of a supreme rule): the legitimate right of a people to self-determination and non-interference.5

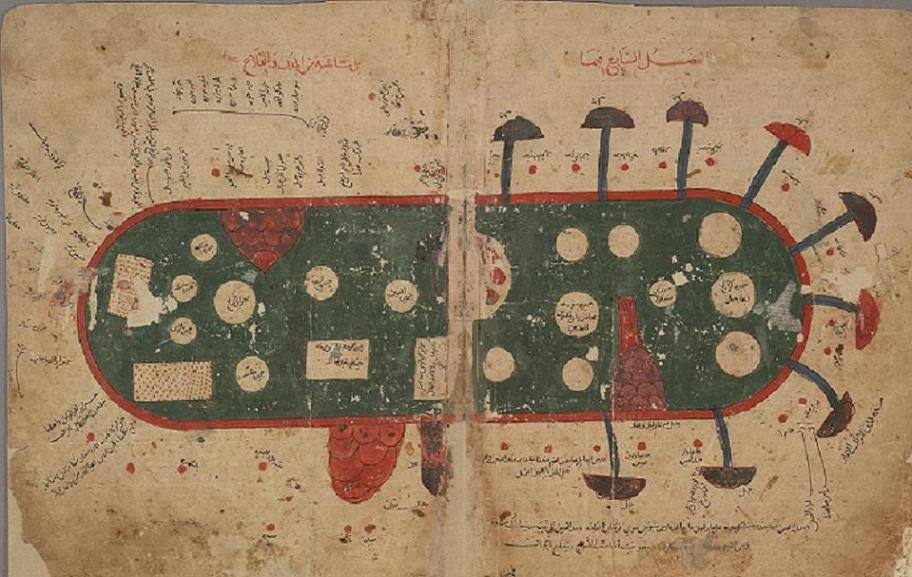

![Historical Map of Balkan Europe 1815 [includes Balkans] (294K)

From 'The Public Schools Historical Atlas' edited by C. Colbeck, published by Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905. Historical Map of Balkan Europe 1815 [includes Balkans] (294K)

From 'The Public Schools Historical Atlas' edited by C. Colbeck, published by Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UUcJ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F32ff92db-fbba-4810-bc84-b6c1edcf21bf_1584x1230.jpeg)

But the idea of the sovereignty of nations belies the fact that nation-states are the very mechanism by which international capitalism operates, continuing the patterns of global exploitation established by colonialism, at the same time as appearing to give every nation power over its own fate. The reason for this affinity between capitalism, colonialism and nationalism despite appearances to contrary (e.g. national laws limiting corporate power, or national independence ending colonial exploitation, or international non-interference aiding peace) lies in the origins of the modern nation as an idea.

In my next post on the narrative of nation I will begin my exploration of these origins by taking a closer look at Benedict Anderson’s seminal work Imagined Communities (1983), one of the key texts that links the emergence of the nation with European modernity.6 This book has shaped my own thoughts on nation, unsurprisingly, as Anderson places language and books at the center of the process of imagining nations.

Despite the popular characterisation of the Magna Carta as a national constitution, it isn’t much more than an agreement between the king and local barons. It was also not particularly unique in medieval Europe. This is precisely how the narrative of a nation works: by retrofitting history.

“Romanovs ruled over Tatars and Letts, Germans and Armenians, Russians and Finns. Habsburgs were perched high over Magyars and Croats, Slovaks and Italians, Ukrainians and Austro-Germans. Hanoverians presided over Bengalis and Québecois, as well as Scots and Irish, English and Welsh.” from Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson, who also notes that what became the late British Empire has not been ruled by an “English” dynasty since the 11th century.

A common language or dialect that is the result of the contact, mixing, and often simplification of two or more dialects.

There were pre-modern states that had democratic elements in India, Mesopotamia and famously in Athens. But these democracies were limited in scope, with large numbers of people without representation (and many enslaved) and were also ethnically heterogenous and territorially unstable.

The idea of sovereignty of the state is often said to have originated in the treaties of the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Year’s War in 1648. Some dispute this, arguing that it emerged later and was, as is the way, retrospectively found to be a historical legacy. This so-called Westphalian sovereignty was (re)articulated in the United Nation’s Charter in 1945. Note in particular: Article 1 (2) - Equal rights and self-determination of peoples. Article 2 (7) - Non-intervention in domestic affairs by the United Nations

Although no means the first or the only. Anderson draws on a tradition of Marxism including Althusser and Foucault, who I will return to. I begin with Anderson because he is specifically concerned with the imaginary aspect of the nation.

Eva, I am so glad I subscribed! This is terrific and beautiful writing on a very complex historical concept.