"How Britain became a migration magnet"

A potted history of migration to the UK in numbers and headlines.

How Britain became a migration magnet under Labour: Net outflows CUT the country's population for a century... before arrivals started to ramp in the 1990s

Mail Online 16 June 2023

It’s true. Historically, Britain has rarely been a net recipient of migrants, and never in such large numbers. Significant numbers did come to settle in the last two centuries, in particular Irish, German and Russian, including many Jews, but many more Brits emigrated, almost always for economic reasons. That doesn’t mean that immigration wasn’t a political issue, but it really didn’t affect population numbers until the influx of migrants from the commonwealth in the 1950s, and the only marginally.

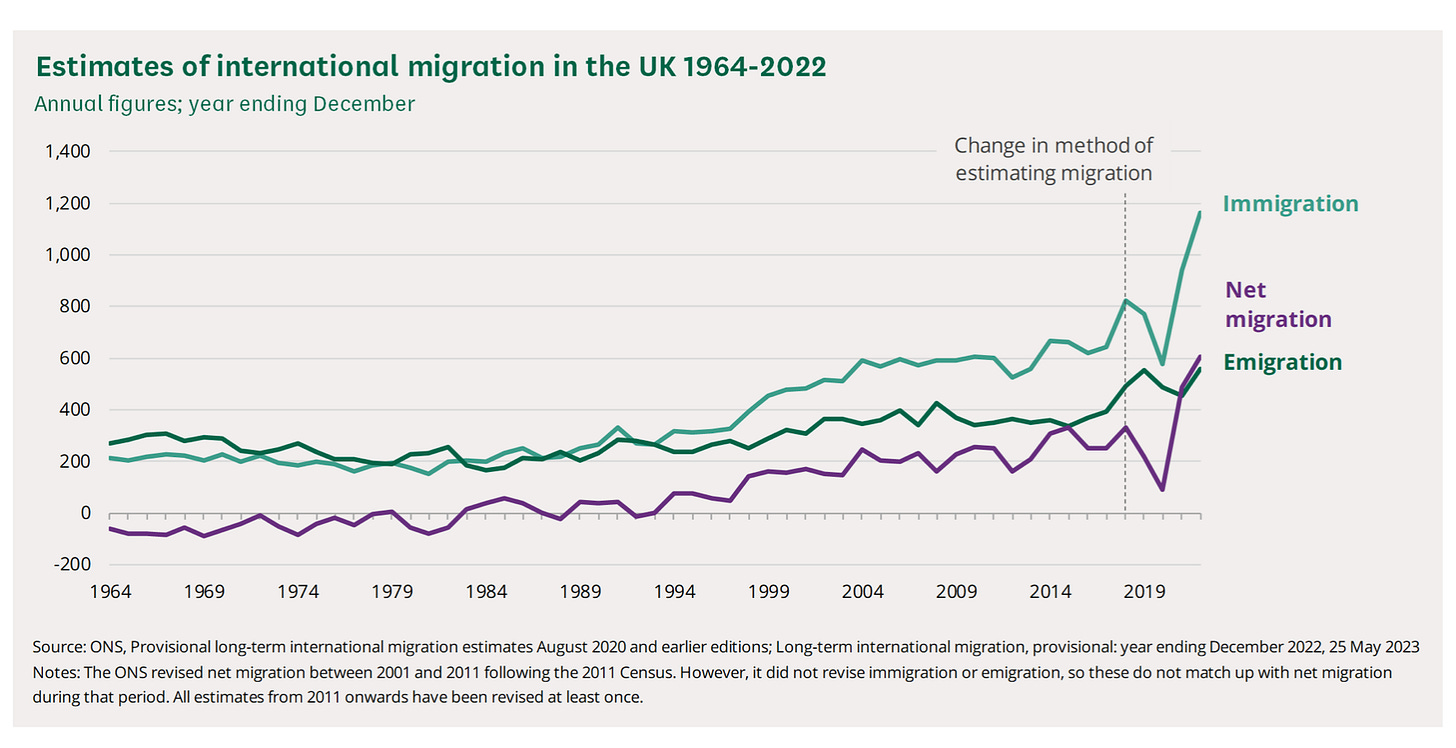

Exact numbers are hard to come by, but there was probably a couple of hundred thousand immigrants of the so called Windrush generation overall, but even more new Brits were born in the same decade, and lots of people left, so net immigration was only in the thousands. After the post-war baby boom peaking in the early 60s, UK population growth slowed: birth-rate as well as net migration plummeted in the 70s, and recovered to an average of just under 100k natural growth per year average in the 80s and 90s and net migration at more or less zero.

I came here on the back of the first post-cold war expansion of the EU in 1995, which included Sweden. I was one of 75,000 total net immigrants to the UK that year. The recent estimates for the last 12 months show an 800% increase on that figure. That spike has little to do with Labour policy in the 1990 and 2000s, and also little to do with Tory policies from 2010 onward. The rhetoric on what kind of migration - EU, non-EU, asylum seekers, “illegal migrants”- is out of control and needs to be cut often misrepresents the actual numbers involved.

Unforgivable. Britain faces a new wave of immigrants from Eastern Europe. It is only a matter of time before this Government's failed immigration policy comes home to roost.

The Daily Mail, London, January 24, 2004

In the late 90s net migration rose steadily, but the dreaded expansion of EU eastward in 2004 only saw a small initial increase after which EU and non-EU numbers plateaued at about 300,000. The financial crisis slowed migration, perhaps from Europe in particular. At no point did EU arrivals exceed non-EU ones until 2012.

Owning a cat helped immigrant avoid deportation

The man, a Bolivian who came to the UK as a student, gave cat ownership as one of "many details" to prove the long-term nature of his relationship, his solicitor Barry O'Leary said.

Independent 19 October 2009

In 2012 EU immigration matched non-EU immigration for a few years, mainly due to new migration rules brought in by Theresa May brought in new rules, which at this stage could only affect non-EU migrants. May limited visas issued to skilled workers, reduced rights for students to bring dependants and to remain after finished studies, and introduced an £18,000 minimum “income” for anyone (including Brits) wising to bring family. In addition the so-called “hostile environment” meant rights to work and stay had to legally checked by all employers.

Theresa May interview: 'We’re going to give illegal migrants a really hostile reception’

Telegraph 25 May 2012

The migrant crisis that affected Europe in 2015, and which many see as contributing to the Brexit vote, caused massive headlines and but only a small spike in net migration, to which continually increasing EU immigration also contributed. In fact the number of asylums seekers to the UK had spiked in the early 2000s at around 80,000 a year, while the 2015 crisis saw about 35,000 applications.

Guardian 30 July 2015

Asylum seekers are a growing but still small part of UK immigration. It is worth keeping in mind that the numbers have been kept artificially low through several treaties with France from the Sangatte protocol in 1991 to the Touquet treaty in 2003, under which the British Government pays France to prevent “irregular migration” to the UK. There are, in effect, very few “legal” routes to claim asylum in the UK, as one cannot do so on French soil, and boarding a vessel or plane to our island nation without a right to stay is almost impossible.

In response to British pressure to cut the flow of European illegal immigrants arriving from France, Calais is trying to drive out waiting asylum seekers by creating miserable conditions.

Guardian 7 Aug 1999

I want to look at this issue closer another time, but in brief as French-British policies have made staying in Calais or crossing by other means more difficult, the number of refugees crossing by boat have risen dramatically. The ONS estimates that the applications this year, 37% of which are arrivals by small boat, will almost match the spike in the early 2000s.

Revealed: immigration rules in UK more than double in length

Guardian 27 August 2018

The one thing that has been a constant is the attempts from governments to curb migration, or at least appear to do so. Brexit was famously going to allow us to “take back control” over our borders. EU immigration spiked just before the referendum, after which, unsurprisingly, the numbers of EU citizens migrating to the UK has fallen sharply causing a panic over labour shortages and a reversal of many of the limits on migration introduced by May.

MPs propose permit-free work for skilled migrants to combat post-Brexit immigration policy vacuum

Independent 19 July 2018

Immigration status: Ministers reverse May-era student visa rules

International students will be allowed to stay in the UK for two years after graduation to find a job, under new proposals announced by the Home Office.

BBC 11 September 2019

Immigration: No visas for low-skilled workers, government says

Low-skilled workers would not get visas under post-Brexit immigration plans unveiled by the government.

BBC 19 February 2020

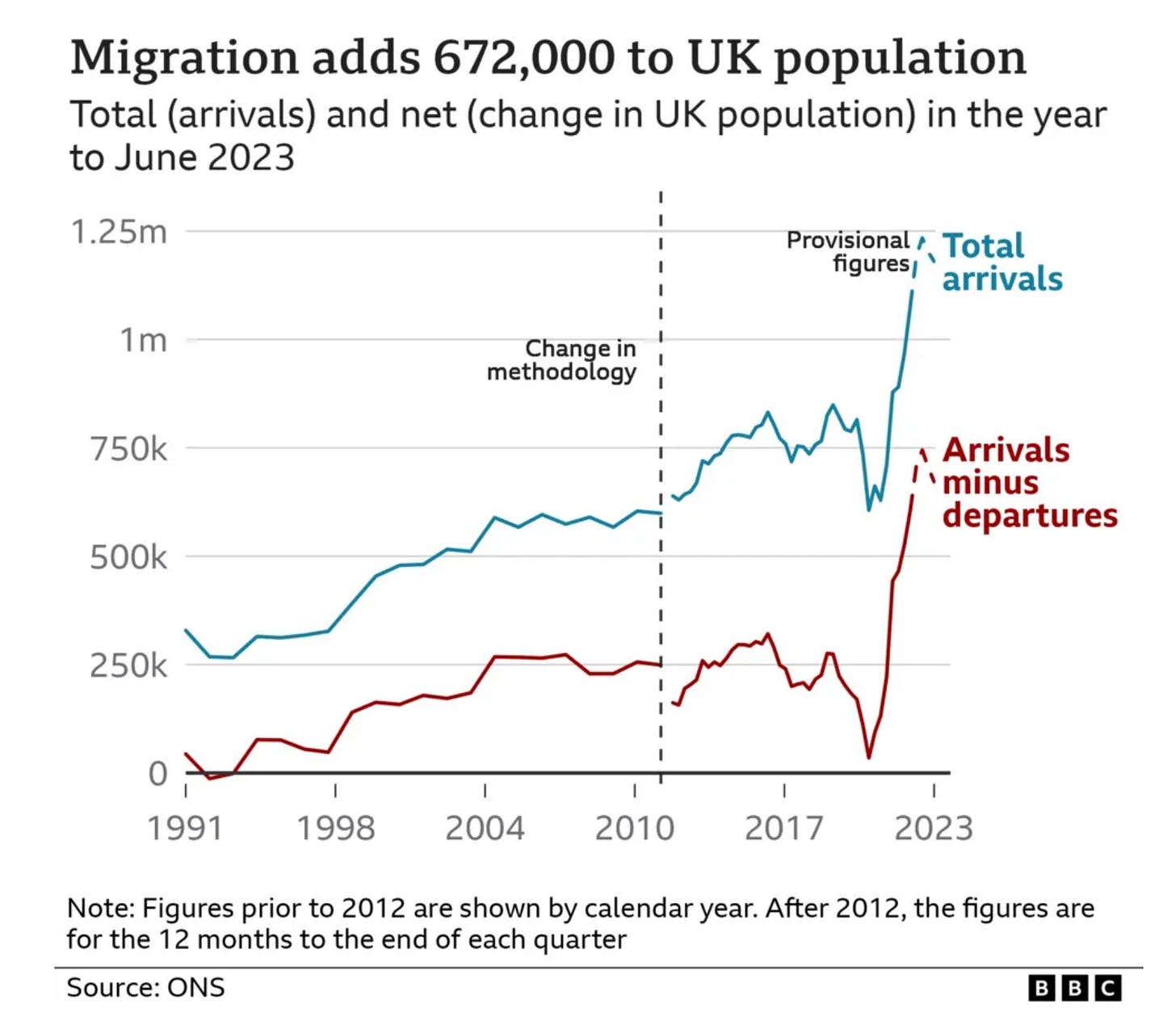

Figures in the past few years are skewed by the pandemic, but notably the 2021 changes to immigration rules, ending the of freedom of movement for EU citizens and introducing a new points-based system which opened up access to work visas, has had an enormous impact. According to the ONS in year ending June 2012 a net number of 57,000 non-EU migrants arrived, while in the year ending 2023 the estimated figure is 768,000. The headline figures of 672,000 include 86,000 EU-citizens and 10,000 British citizens leaving.

It is notable that a large proportion of of non-EU migrants to the UK are students. In fact, these have been the largest part of net migration figures, except in this last year’s estimates in which work-related migration exceeds students by only 15,000. An estimated 378,000 study visas will have been issued year ending June 2023, while five years ago that number was 127,000. This is something I want to have closer look at in terms of the UKs policy on higher education, but that will have to be a different post.

The response of the government to the latest figures has partly been a knee-jerk attempt to cut legal migration and partly increasing bluster around “illegal migration” and the scheme to deport such migrants to Rwanda. The Rwanda farce probably also deserves a whole post on its own, but let’s just note that initial stages of the controversial scheme makes provision for 200 deportees. The idea to make all arrivals by small boats “illegal” by denying them possibility to apply for asylum would mean at least an additional 40,000 people to deport.

One-way ticket to Rwanda for tens of thousands of Channel migrants.

The Telegraph 14 April 2022

The new proposed measures to curb legal migration feel like we’re on a merry go round that is taking us back to 2012, except without the EU folk to fall back on. Apart from the fact that the UK economy is unlikely to do well without migrants, the very idea that we can “curb” migration now seems as preposterous as it was then. It seem increasingly anachronistic to pursue a rhetoric which implies that immigration is on the one had a bad thing, and on the other, can and should be “controlled”. I think it is time to realise that those two narratives are increasingly untrue.

Increase in sponsor earnings from £18,600 to £38,700 will prevent up to 70% of workers in UK bringing in family, data shows.

Guardian 5 December 2023

The world population grew from one billion in the early 19th century to five billion in 1987, it increased by another billion by 1999 and another two since then. International migration has doubled globally since 1990 and yet only about 3% of the world’s population live in a country different to the one they were born in. Disregarding national instability and international conflict the climate crisis alone means there is a lot more to come.

What is surprising is not how big the amount of people coming to Britain in the last few decades is, but how small.